IRWIN KREMEN

Furthermore

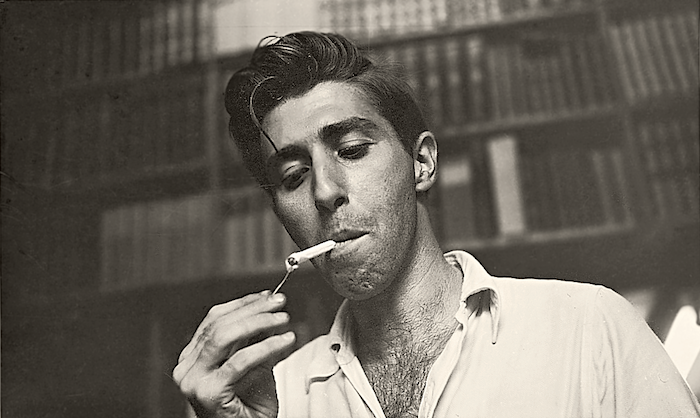

Irwin Kremen

From That Day

to This

Prologue

Scan the titles of the works in this [Nasher, 2007] exhibit. Only a few1 match particular visual elements in the works they name. That’s how we — Barbara and I — craft titles. Carefully. We seek identity tags for nonrepresentational works that can leave them free perceptually and associatively. Our aim is thereby to prevent entanglement by specious idea or otherness.2 This requires a fit of words to objects that renders the verbal meanings perpendicular to the art’s visual contents. Our collaboration is playful: that of a poet and an artist in quest of succinct words or double meanings or ironic tropes to mark works that remain in effect silent. I much value Barbara’s sensibility and acute intelligence, her mastery of the well-wrought phrase and telling pun that is manifest in her writings.3 But who is she? My art making began with her. Therein lies a tale. . . .

I

During the fall of 1951, a period of uncertainty for me, when I lived in Greenwich Village, M. C. Richards, luckily, came to town from Black Mountain College. She had been my literature instructor there, and after I left we remained close. I naturally began hanging out with her and thus also with her friends: the pianist David Tudor, with whom she then was living; the composer John Cage; and the dancer-choreographer Merce Cunningham. Letters to me from Black Mountain in the late forties had described visits there by John and Merce and the stir made by John’s performances on the prepared piano. Now, in late 1951, and working on parts of his Music of Changes, John several times played newly composed portions of it for me. Part I was premiered by David in a New Year’s concert at the Cherry Lane Theatre. A different program was scheduled for early February,4 and John handed me a complimentary ticket for it. I had no idea how momentous my attendance would prove.

M.C. and I went together. She sat in the first row of that cramped theater, I right in front of her at the end of a tiny bench in the prompter’s box. On looking over the other three sitting there, I spied at the opposite end a woman of such great beauty that I turned to M.C. and pointing, said, “Oh, look, I’m a goner!” Whatever led me to blurt that out with such immediacy and certitude I’ve never known! But as it turned out, that sudden intuition was predictive. I didn’t need the urging M.C. gave me at intermission “not to let the pretty one get away,” for I quickly headed to the small lobby and accosted her, babbling some inanity by way of introduction. Barbara Herman had come as a guest of Stefan Wolpe,5 whose music was also being played that night by David.

M.C. and I went together. She sat in the first row of that cramped theater, I right in front of her at the end of a tiny bench in the prompter’s box. On looking over the other three sitting there, I spied at the opposite end a woman of such great beauty that I turned to M.C. and pointing, said, “Oh, look, I’m a goner!” Whatever led me to blurt that out with such immediacy and certitude I’ve never known! But as it turned out, that sudden intuition was predictive. I didn’t need the urging M.C. gave me at intermission “not to let the pretty one get away,” for I quickly headed to the small lobby and accosted her, babbling some inanity by way of introduction. Barbara Herman had come as a guest of Stefan Wolpe,5 whose music was also being played that night by David.

The concert over, I bird-dogged Barbara out of the theater and, knowing that both the Cage and the Wolpe contingents were headed to the Cedars Bar,6 I managed to get into the same crowded cab as she. The press was great, and I recall she sat perched gingerly on my lap. At the Cedars we dispersed to different tables, she to be with Wolpe and his wife, the poet Hilda Morley, and their guest Dylan Thomas; I with my friends, the Cageians. But having no money on me, what to do? The only thing, to borrow a buck from a friend. With that I got a draft for myself and a cognac for “the pretty one,” which I took over and wordlessly plunked in front of her before rejoining my friends. I had just enough change left to escort her after the party to 87th Street, where she lived, and still get back down to 11th, where I did.

On that subway ride uptown and in the days that followed, I learned much about Barbara: of her literary interests; of her current work as a research assistant and writer at the Metropolitan Museum of Art; of her schooling at Bryn Mawr, Harvard, and the Sorbonne; of her wartime stint in the WACs on the staff of the Army News Service; of the years she lived afterward in Paris and Ascona, Switzerland. Her mix of experience, complementing her beauty, enticed me all the more. So I phoned two evenings later and arranged a short visit for the following. There, in her library, sat many an interesting volume, multilingual. One book particularly whetted my fancy. She owned a copy of Finnegans Wake! Me, oh, my, so did I, and had long wanted to tackle it. Perhaps we could read it together. But to propose that would be too obvious. Better several of us. A natural would be M.C., with whom I’d read Ulysses at Black Mountain, and maybe John, who had written a song for lines from the Wake.7 What a ball, to read that astounding work out loud, every word, discussing it as we would go along. It would take months! Pronto the next day I began work on it. M.C. gleefully approved; John however couldn’t commit to a project so dauntingly long;8 Barbara, to my delight, was interested. Inviting her to dinner at my place, I arranged also that the first reading take place there immediately after. And so began a great adventure, twofold in scope: an indwelling in Finn and the forging of a bond with Barbara, intense, exciting, amorous, and deep. Having met in February,9 we were a couple by May. Then she had to go to Harvard for two courses needed to complete a master’s. On her return to New York after Labor Day she found, lying on the table in her apartment, a collage I made to welcome her back — my first. Fourteen years elapsed before I would venture another!

On that subway ride uptown and in the days that followed, I learned much about Barbara: of her literary interests; of her current work as a research assistant and writer at the Metropolitan Museum of Art; of her schooling at Bryn Mawr, Harvard, and the Sorbonne; of her wartime stint in the WACs on the staff of the Army News Service; of the years she lived afterward in Paris and Ascona, Switzerland. Her mix of experience, complementing her beauty, enticed me all the more. So I phoned two evenings later and arranged a short visit for the following. There, in her library, sat many an interesting volume, multilingual. One book particularly whetted my fancy. She owned a copy of Finnegans Wake! Me, oh, my, so did I, and had long wanted to tackle it. Perhaps we could read it together. But to propose that would be too obvious. Better several of us. A natural would be M.C., with whom I’d read Ulysses at Black Mountain, and maybe John, who had written a song for lines from the Wake.7 What a ball, to read that astounding work out loud, every word, discussing it as we would go along. It would take months! Pronto the next day I began work on it. M.C. gleefully approved; John however couldn’t commit to a project so dauntingly long;8 Barbara, to my delight, was interested. Inviting her to dinner at my place, I arranged also that the first reading take place there immediately after. And so began a great adventure, twofold in scope: an indwelling in Finn and the forging of a bond with Barbara, intense, exciting, amorous, and deep. Having met in February,9 we were a couple by May. Then she had to go to Harvard for two courses needed to complete a master’s. On her return to New York after Labor Day she found, lying on the table in her apartment, a collage I made to welcome her back — my first. Fourteen years elapsed before I would venture another!

That long interim served me well, as under Barbara’s influence my life turned around decidedly. Vague ends faded, replaced by feasible goals. She got me finally to finish a B.A., and that led to graduate school, where I flourished intellectually in the stimulating interdisciplinary atmosphere prevailing then in my department at Harvard. Married less than a year when I entered, we left with two children, to begin an academic career that further expanded my intellectual horizons and range. But unpredictable altogether was my turn to art making in 1966. From that day to this,10 over forty years!

The story how that began I’ve told before:11 that M.C., who visited us that June, enticed me to make a cloth collage; how after she left I tried making another, now from papers, but what a disaster; that weeks later, as planned much earlier on Barbara’s instigation, we spent six weeks in Europe, it leading to another momentous turn in my life, for on seeing many collages by Italo Valenti during a long stay in Ascona,12 I apparently grasped what was needed for the making of a coherent work; and how on returning home I began playfully to make works in the hope they might grace Barbara’s home, much as art did in those of her Swiss friends. Never mind that her home was mine too. Whatever else at that time pushed me to the making of art, I know that it was for her also that I began. Nor has that changed to this day. She’s my primary audience—the first to whom I show new work and the only one to see some in various stages of their becoming. And when on occasion a work doesn’t quite pass muster with her, that is, if she feels it’s not finished, I almost always continue working on it until it is. From the beginning she applauded my venture into art and has sustained and helped me immensely since.13 Fifty-five years with her, forty in art making. . . . I’ve been fortunate indeed.

II

Gather Your Days is a collage made in 1973. The title, but not the collage so named, refers to a bit of Kabalistic lore presented in a talk the following year at Duke’s Center for Jewish Studies by the renowned authority on Jewish mysticism Gershom Sholem, according to which at the moment of death all one’s days gather briefly about one’s unencumbered soul. To experience such a totality, even momentarily—each day integral in its singularity, all gathered about the centrality of one’s being, womblike, comforting yet epiphanic—what an enormously appealing conceit! A pity it holds no hope for me, who accord no credence to occultisms of any kind, whether souls or spirits, gods or whatnots. The closest I could approach that Kabalistic conceit would be a retrospective exhibit of my work. It could provide a taste, an iota of that implausibility. Spread over time, moreover! The selection process, requiring a review of one’s entire oeuvre to that point in life, would itself take months. Afterward, with the art hung, one could stand in the gallery surrounded by the fruit of one’s former days and ways, frequently and longer than momentarily.

Such is this exhibit for me.

A great many works,14 diverse in kind—of collage, painting, sculpture, mixed media, sketches, unclassifiable objects, assorted ephemera—were reviewed by Dr. Sarah Schroth, the Nasher Museum’s senior curator, and me prior to the final selection for this retrospective. The diversity wasn’t surprising though the extent was, and it provided me with a view of how I had partially15 measured out the last half of my life—in play, exhilarating and deeply serious. About that playing I had earlier written: “I go until I have what I want—my kind of a collage. Its emergence is always marvelous for me. I cannot predict its particular coherence and beauty from its inception—at the end, it is often radically different from its beginnings—but the process is not trial and error either. I begin the work with what is phenomenally real before me. I know what I want to happen, though I have no specific design in mind, nor could I put in words what it is I know. The process is a concretization of it and is its own articulation.”16

So I count myself privileged in having been privy, during the past four decades, to the making of that body of work. Many were the times when, late at night, in the solitude of my studio, the emergence of a striking collage-of-my-kind would spontaneously set me jubilating, and I would sing or dance a little jig or chant in Yiddish-like nonsense syllables. Asked years ago whether that knowing of which I speak resembled whatever guides a bird in the construction of its nest,17 I could venture no answer, nor would I now. Any supposition would have had to rest on terms either mechanistic or functional or platonic or dialectical—ultimately metaphysical, whichever, and to my thinking better avoided.

The word “beauty”18 and its cognate “the beautiful” have been suspect, derogated and excommunicated for long in praxis and discourse, both for good and for poor reason. For my part, in beginning any work my implicit intent is always to fashion an intensely beautiful object — “implicit,” because I never instruct myself beforehand to achieve that; nor would it help, since at the time I can’t know until the end what may be achieved. The intent operates automatically whenever I want simply to make another work and commence doing so. If I’m successful or, better, when I am, the finished work, its beauty and the feeling it arouses, constitute the meaning(s) of the work for me, however unnamable. I have found that this being so, others too apparently have strong positive, and some claim emotional, responses to the work—but what that may be is not for me to say. The beauty of which I speak—whether a quality of collage or painting or sculpture—runs very generally, I feel, parallel to my fierce sense of the dearness of life, this against the ground of death’s inevitability, a connection that’s never consciously in mind when I am working. In saying “parallel,” don’t mistake me: I mean separate and independent though related. The one does not symbolize or represent or act as metaphor for the other.

With few exceptions19 works of mine refer to nothing beyond themselves. They are not literary. They do not refer, do not picture, do not symbolize, are not tropes or metaphors. They are not about, they are. Each is its own content, a presentation, not a representation. Most call them “abstract” but I don’t, preferring instead the designation “nonrepresentational.” A work-of-my-kind is particular, singular, idiographic. It shares the condition of music, its meaning being complex. What that may be can no more be put into words than it can for, say, a Rasumovsky or a late Beethoven quartet. The nonrepresentational mode frees me in ways that I highly value. For one, it allows me to make an art that demands no particular kind of response from a viewer, nor seeks to push toward some partisan idea, aim, or position. It leaves the viewer free, in what can be a delicious freedom unconstrained by necessity; for in the care-ridden quotidian ruled by desire and constraint, the undriven moment can enhance living. And by not depicting or symbolizing or functioning as metaphor, it ought to forestall interpretation about and imputation to me of intentions, motivations, meanings, fantasies, unconscious states, beliefs, ideological leanings, programmatic loyalties, or anything of that ilk, psychological, political, or otherwise.20 Which leaves me free too, though quixotic perhaps, in view of the need by art mavens, as well as others, to make something of a work other than what it is.21 I’ve done all I can to countervail that, proclaiming in essay after essay and in many lectures the fundamental nonreferential basis of my work and the need to perceive any one as the singular object it is before enmeshing it in personal associations.22 But people don’t seem to read or listen, or if they do, don’t attend seriously to what I’ve said. Instead they go off interpreting via unstated criteria and nonreplicable association chains. Whether in the short run or long, I expect misprision is unavoidable.

III

During the first feverish months of art making in 1966, I used over twenty-two different kinds of materials or media in what I made. I was free to do so for two reasons: first, because at Black Mountain I knew that Josef Albers’s students had made what were called matières, compositions from a multitude of unusual materials. And, second, I knew that Cage had written music for the piano that modified its sounds by the attachment of different objects to the strings. And I was very familiar with the work Cage often claimed was his most important, the one in which any contingent sound occurring at the time of its performance belongs to it: his notorious 4’ 33" or “silent piece,” which is dedicated to me.23 To this day I retain that freedom. At a recent New York exhibit of my late work, thirty-three different media were listed on the labels. On those of this Nasher exhibit, ninety-four are to be found.

In the fever of that beginning, I adopted three rules to minimize, even eliminate, certain potential influences on me. I was not to consult the empirical literature on the psychology of visual perception, not to peruse art magazines, not to make anything similar to a Valenti. These strictures served me well and for long, and though they became anachronistic many decades ago and, if I wish, can be violated at will, in the main I adhere to them still. The first aimed to guard against the suggestive force that generalizations from experimental data might bear on my behavior; the second, against the fickle seductions of fashion; the third, against the pull Valenti’s work might exert to imitate it. Though I was early able successfully to avoid that pull, nevertheless he influenced me at two crucial points.

On our way to Spain for a month during the summer of 1967, we stopped first for a week in Sils Maria. Knowing that Valenti and his wife, Anne, would join us there, I prepared slides to show what I had finished since beginning art making the previous October. I took them along with trepidation, because the year before I had seen Italo enter an Ascona gallery where a friend of ours was having an opening and, with only the quickest of glances at the collages on the walls, leave immediately in disapproval. Whatever possessed me to bring those slides?! Had Valenti disapproved, had he given the faintest sign of dislike, I almost surely would have quit making more art. But he in fact met my showing with generous enthusiasm and emphatically urged me to continue, counseling that I take the work called S/G (Avanti), one of the earliest in this exhibit, as touchstone. This indeed was influence—not regarding the usual loci, on that of style, content, or composition, on form, color, texture, or material—but on function, on the continuation of art making itself.

Another huge change in my life—indeed an adventurous one—began a decade later. In 1976, during a summer in France, I made sixteen collages, followed by twelve more in Ascona during May 1977. Together,24 this represented a major increase in my powers after a relatively dry period earlier in the seventies, when my attention was focused elsewhere, for almost everything I now touched turned into a collage-of-my-kind. I never intended to be an artist, never had the least ambition that way, and now I knew I had truly become one. But I had resisted for ten years—assiduously—all suggestions that I undertake any exhibit of my work. Strong coaxing was needed for that, and Valenti ably prodded me toward the first ones. I’ve written elsewhere25 how that happened and about his major role in it. Briefly here, on seeing the twelve Ascona collages and given their quality, he insisted that my responsibility unequivocally required that I show it publicly. No other at that time, except possibly Cage, could have persuasively impressed that on me. Again an influence by him on a process complementary to art making.

From time to time, the question of influence comes up in a review or is put to me by others. What is adduced or wanted in reply are citations of, or presumed similarities to, celebrated artists. Most of that is wildly besides the point. “Influence,” in my experience, is a factor acting as enticement to work. When moved to admiration by art recently seen, I itch subsequently to make a work of my own that, though radically different, would be of comparable quality. But mind me, I’m not saying “equivalent” nor claiming achievement of any such comparability. That itch has often assailed me as we have traveled widely and seen much art in various contexts and in situ. My familiarity with art ranges over many cultures across space and time, from Paleolithic cave paintings26 to work of the near present. A corollary of the wish for comparability is that the work be worthy also of a place within that long line, beginning from the Magdalenian. The influence on me as an artist, then, is not piecemeal, not of some feature from another artist’s work here, nor of some stylistic element there, but is a silent and invisible resonance with great human works of the past, leading not to imitation—but toward transformation.

Epilogue: The Irwin Kremen/William Noland Sculptural Collaboration

.jpg)

For the catalogue of a previous exhibit27 I wrote at length about my involvement with sculpture and told how my friend William Noland, professor of sculpture in Duke’s Department of Art and Art History, induced me to undertake increasingly larger sculptural challenges. Shortly after I wrote about that, he and I began collaborating on the large sculptural ensemble we call still [untitled], which is concurrently on view in the Great Hall of the Nasher Museum. He and I have jointly made three other large-scale sculptural works, two of which, [III] and Too, are on exhibit also. The Kremen/Wm. Noland collaboration (K/Wm.N) has few sculpture-making precedents historically. During our ten years or more of collaborating in relative isolation, we made every compositional decision together. The result is a body of monumental sculpture that now can be seen by others.

[These sculptures are identified and shown larger on the Kremen/Wm. Noland page.]

That resonance of which I spoke earlier is operative here too—in effect, it is joint, as it now includes that which affects Noland also. Our touchstones are ruins, temples, cathedrals, friezes, piazzas, Japanese gardens, welded-metal and site-specific sculpture, among others. The K/Wm.N collaboration has not only extended but has also moved beyond what is canonical to it, in fact, beyond sculpture in its usual mode. Whereas a single sculpture presents itself to a viewer in the round via front, back, and sides, we have constructed sculptures that in addition provide a multiplicity of other possibilities. This has been accomplished through “open composition,” by which is meant the arrangement of large sculptural units vis-à-vis each other, with open spaces interspersed between them as well as within the ensemble. These open spaces, now integral aspects of the work itself, offer ingress points to viewers who can move not only circularly, as before, around the perimeter of the work, but also into and within it. The component sculptural units, being precisely composed and fabricated relative to each other and to the entirety, can be maintained exactly as such at whatever site they are placed by virtue of special templates built to ensure that. What can transpire, then, for a viewer anywhere is the possibility of a perceptual encounter with the work from multiple points and angles internally and externally—or, in short, a situation much altered from that of conventional three-dimensional sculpture and, accordingly, with attendant enlarging of the aesthetic experience. A contributory strand to that experience relates to the surfaces of the works that we make. Again, these depart from the usual, which generally obliterate the “history” of the material, whether from facture, chance accidents, or weathering. But our sculptures, for the most part, retain them all, except where they impede the perceptual unity or the quality of the work, in which case they are altered or discarded. Thus, while the K/Wm.N sculptures seize attention by their monumental presence, the plenitude of surface detail beckons the viewer to approach closer for a keener perceptual and hence aesthetic encounter.

More about Noland, taken from the essay referred to at the beginning of this epilogue: “I owe a lot to Bill [Noland]. In ’89 he pushed me to collaborate on the design of a city plaza for which we made two sculptures together. Thereafter, he’s coaxed me into one situation after another in each of which I’ve made a number of works progressively more ambitious. First, he suggested that I work in the old Duke sculpture studio during the summer in ’90; then, the following year, he urged me to take over the lease of his old studio when he was moving out; then, he offered me the use of [a] commodious new studio this past summer [’95]. Each proposal of his would put me on my mettle initially. I would feel somewhat uneasy because I couldn’t be sure I’d be up to its challenge. I might have balked had he not persisted in his low-key but determined way. Because I emerged each time successful, at least according to my own standards, [one] can understand how grateful therefore I am to him. . . . A friend who can do that has got to be the best kind to have.”

Durham, North Carolina

Summer 2006

Notes

1. The collages of the Re’eh Series are the major exception. An inventory of the iconographical program that informs them appears in this catalogue as part 2 of my essay “On the Making of the Re’eh Series and Its Iconography.”

2. For a fuller presentation about how we title and the rationale of our method, see my essay “Word and Collage,” in 53 Collages by Irwin Kremen (East Lansing: Kresge Art Gallery, Michigan State University, 1979), 3–14.

3. Particularly, The Damsel Fly and Other Stories (Seattle, Wash.: Ravenna Press, 2006); “Tree Trove” (a novella), St. Andrews Review, no. 28 (Laurinberg, N.C., 1985); Out of (poems) (Milan, Italy: Lucini libri, 1996; reissued Seattle, Wash.: Ravenna Press, 2006). The Damsel Fly and Other Stories contains four illustrations by me, all of collages in this exhibit: Settignano IV, de novo, Lungarno, and Make Fast [and shown in the collage section of this website].

4. February 10, 1952.

5. Wolpe was a faculty member at Black Mountain during its final years; his connection to Barbara was through mutual Swiss friends, particularly the composer Wladimir Vogel.

6. A favorite hangout of artists, celebrated and otherwise, during the forties and fifties.

7. The Wonderful Widow of Eighteen Springs, for voice and closed piano, 1942.

8. Actually it took over a year-and-a-half to finish. Our readings often were followed by dinners at which Tudor, Cage, and Cunningham—one or another or all three—would join us. Several times I suggested that John read Finn in its entirety. Many years later he “worked through” the Wake in writing mesostics from it.

9. All subsequent readings took place at her apartment.

10. Echoes the title of this essay, which also is the title of a collage in this exhibit [and shown in the collage section of this website].

11. See Irwin Kremen and Janet Flint, “Why Collage?,” in Collages by Irwin Kremen (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1978), 15–18.

12. During the late forties, Barbara lived for two years in Ascona, where she made close friends, particularly with Aline Valangin, a poet, novelist, and Jungian analyst. This was our second month-long stay there, the first occurring in 1957 while I was in graduate school. She led me that summer on a mini “grand tour,” my first trip abroad—to Paris, Autun, Vezelay, Dijon, Ascona, Milan, Verona, Venice, Ravenna, Siena, Florence, Arezzo, Assisi, and London.

13. The instances in which she has helped me are too many to enumerate. One example should suffice to illustrate the length Barbara will go to support what I do. Despite my reluctance, she adamantly went about transforming our two-car carport into a suitable, and at that time spacious, studio for me, by designing and then finding, hiring, and supervising the construction workers. The studio was finished in 1977, only a few months before I was approached regarding the possibility of the first exhibits of my work—at the Southeastern Center for Contemporary Art and the National Collection of Fine Arts. Without the availability of the studio, I could not have made the collages ready for exhibit.

14. My use of the word “work,” here or elsewhere, is not intended to mean or imply that the object so designated represents an embodiment of “art absolute,” as seems often to have been the case during the past two centuries. (See, e.g., The Invisible Masterpiece by Hans Belting [Chicago, Ill.: University of Chicago Press, 2001].) In my usage the word simply refers to an art-object-of-my kind, without surplus meaning.

15. “Partially,” because my life has involved much else, not the least being an intense family life, a rewarding intellectual one, and the excitement and pleasures of many trips.

16. “Why Collage?,” 22.

17. By my dissertation mentor at Harvard, the late Professor Richard L. Solomon.

18. In no way do I subscribe to the Platonic notion of beauty, as proposed by my old and dear friend, the late M. C. Richards, who wrote in the catalogue of the first exhibits of my work that I had spent twelve years “watching Beauty clothe herself.” Nor do I hold an alternate metaphysical notion, lest it lie hidden—meaning unanalyzed critically—in the language I use to think about the concept of “beauty.” A problem with any attempt to offer a definition of beauty—and innumerable people have—is that properties would have to be abstracted from historical exemplars to date, but the series, being open-ended, could not encompass what is yet to be. Still, I can offer a limited definition for my own work and for my own work only: what is known as an ostensive definition, that is, one made by demonstratively pointing (which is what an exhibition is after all, especially a retrospective).

19. Nevertheless, I’ve made a small number of works which, though largely abstract, refer to horrific historical events; specifically, the eleven collages of the Re’eh Series, a memorial to the victims of the Holocaust, and two works whose subject is the World Trade Center bombing, A 9/11 Collage and

A 9/11 Sculpture. All are included in this exhibit [and also in the relevant sections of this website]. A few other works, mostly sculptures, bear titles related to their quasi-figural forms.

20. Here’s an example of an egregious imputation stemming from an interpretation based upon a presumed equivalency, easily shown to be invalid, between a hypothesized part of me and a panel of an early painting in this exhibit. Turnaround [shown in the painting section of this website] consists of two small painted panels, each mounted so it could be rotated on its axis. In the late sixties, after finishing a work, I would hang it in my office at Duke, where I was the director of the Graduate Clinical Psychology Training Program in the Department of Psychology, and colleagues, graduate students, and visitors who scrutinized Turnaround were told that if they wished to change “the world,” so to speak, they could by turning the panels however they wanted, and many did with glee. One day an esteemed psychologist and theorist from an Ivy League university came to my office and, seeing that the left section was turned about thirty degrees relative to the vertical position of the panel on the right, exclaimed, “Krem, your unconscious is askew!”

21. Consider the inappropriate leap this mismatch entails: Years ago, when seeking to characterize my weathered papers, Barbara suggested calling them “experienced.” This designation was often quoted in stories and reviews. Nearly twenty years later, I was stunned to hear a participant at a symposium on my work turn that trope into a symbol of human renewal. As I recall, this speaker likened the battered paper that is transmuted within the beauty of a collage to our lives, which, prone to the knocks of human living, can overcome them and emerge renewed. An amazing misconstrual! Neither my intentions nor anything in the visual content of my works can sustain that, only someone’s projection of personal ideas, fancies, or concerns. As I have written, what happens to those “experienced papers” within any new work is that they lose their former identities in “the collage’s coherence, and their battered and grungy aspects, testaments per se to transience and decay, recede before the visual élan of the whole” (SE Ǝ: Collages by Irwin Kremen [New York: Brooklyn Museum, 1985]).

22. See, for instance, “Works and Ways,” in Irwin Kremen (Birmingham, Ala.: Birmingham Museum of Art, 1981), 5–10; “I & K: A Dialogue,” in SE Ǝ: Collages by Irwin Kremen, 4–13; and “Word and Collage,” 3–14.

23. Cage gave me the score in proportional notation as a birthday present. See the published score, Editions Peter No. 6777a; and the later version, Editions Peter No. 6777.

24. Some of these are included in the present exhibit.

25. See my essay “Out of the Cookie Box into the Frame,” in From the 2nd Decade: Collages by Irwin Kremen, 1979–1989 (Winston-Salem, N.C.: Southeastern Center for Contemporary Art, 1989), 3–6.

26. Following the meeting with Valenti in Sils Maria, we visited the Altamira cave in Spain, and, seeing a small display of seashells used as mixing palettes by those Paleolithic artists, I collected colored earth pigments from nearby cliffs on the Cantabrican coast. Once home, I ground those pigments, mixed them with acrylic medium, and used the resultant paint in the painting Then Is When. This work was the first to be made after Valenti chose S/G (Avanti) as a touchstone for me. [Images of both works appear in this website.]

27. See my essay “I & K: The Fourth Dialogue,” in C#: Collage and Sculpture by Irwin Kremen (Greensboro, N.C.: Green Hill Center for North Carolina Art, 1996), 1–17.