IRWIN KREMEN

The Re'eh Series

I: On the Making of the Re'eh Series

II: Iconography

Photographic Credits

Exhibitions of the Re'eh Series

The Re'eh Series

-

Re'eh: Without a Name

1982

paper

5 7/8 x 5 15/16 in. -

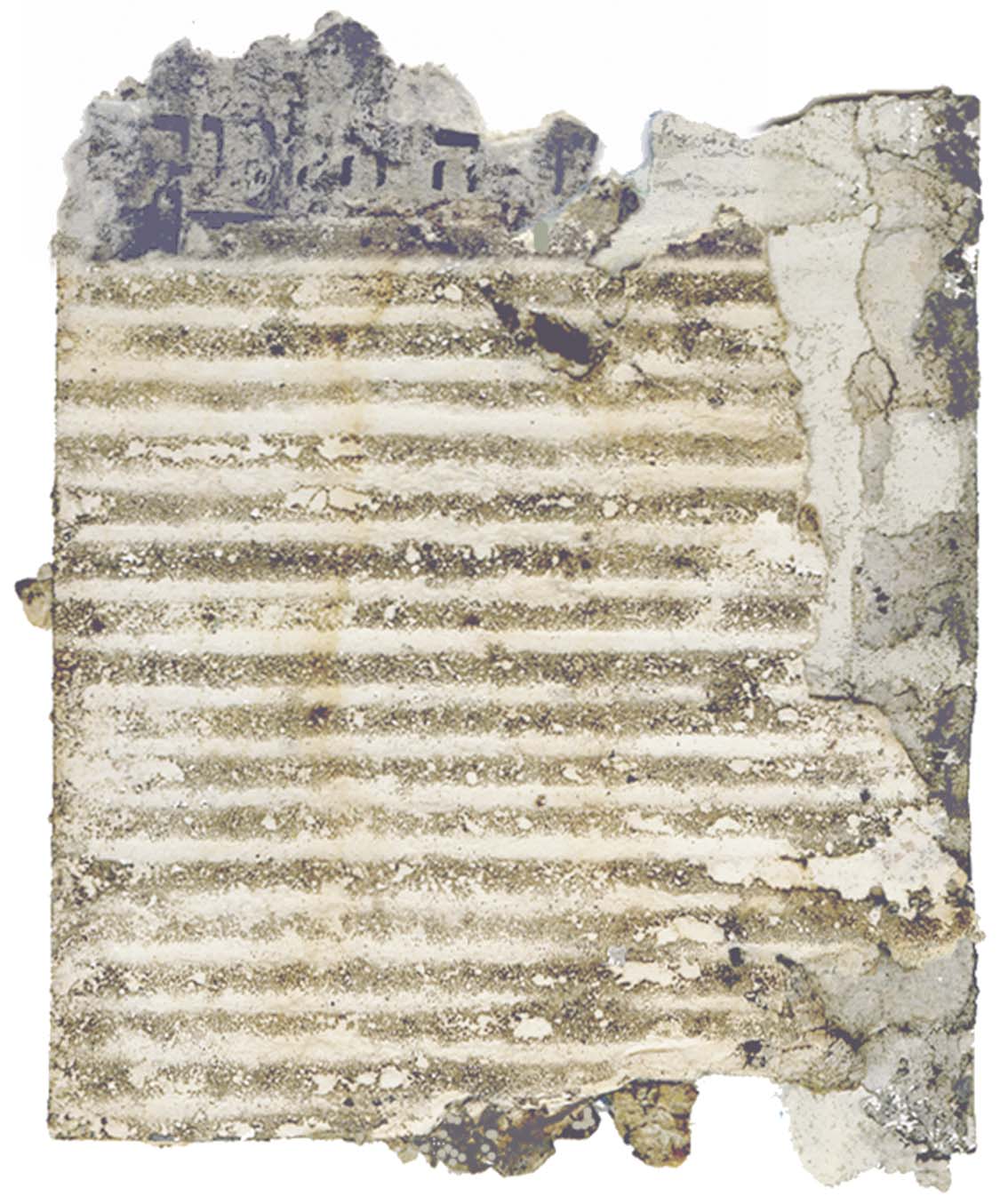

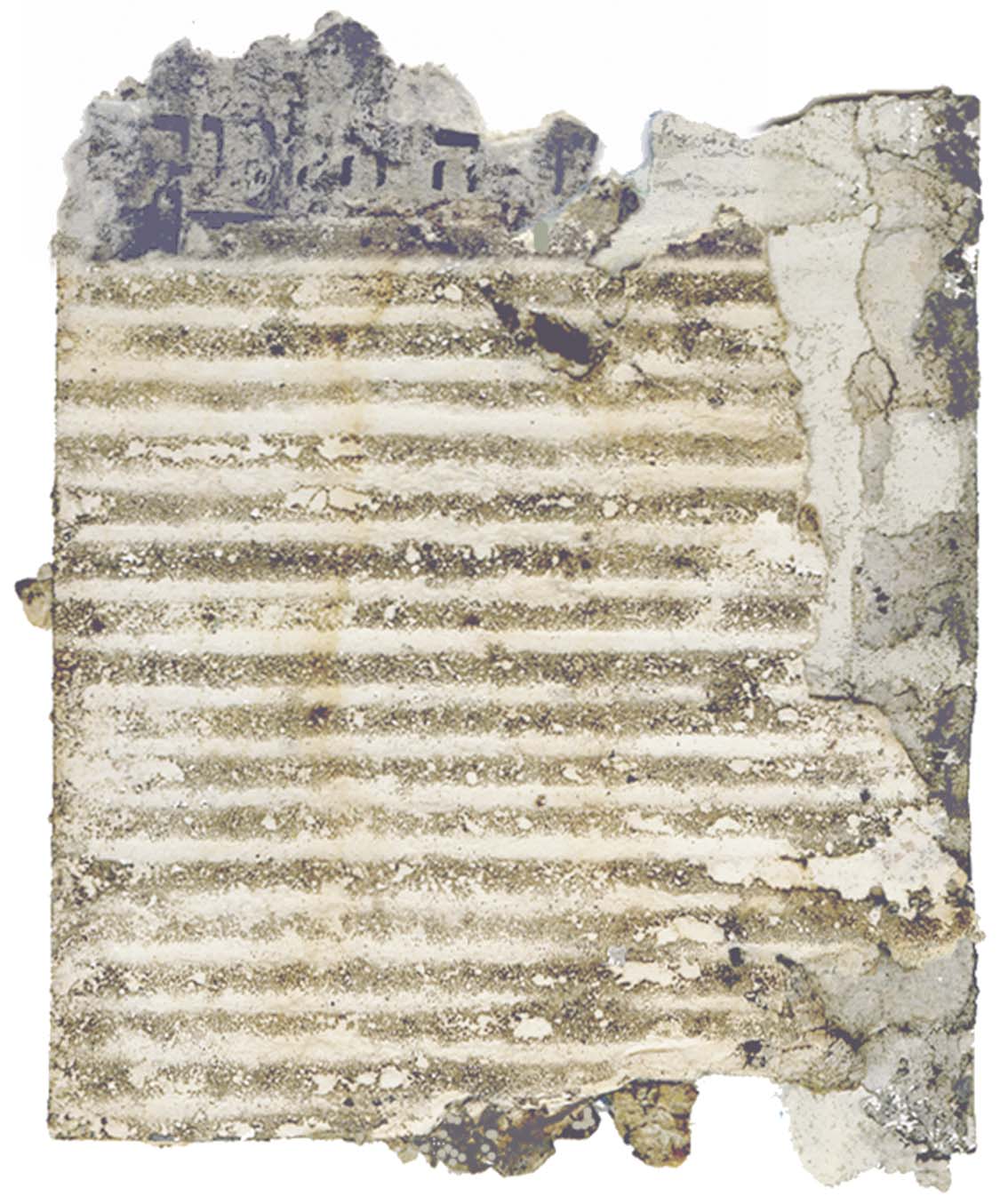

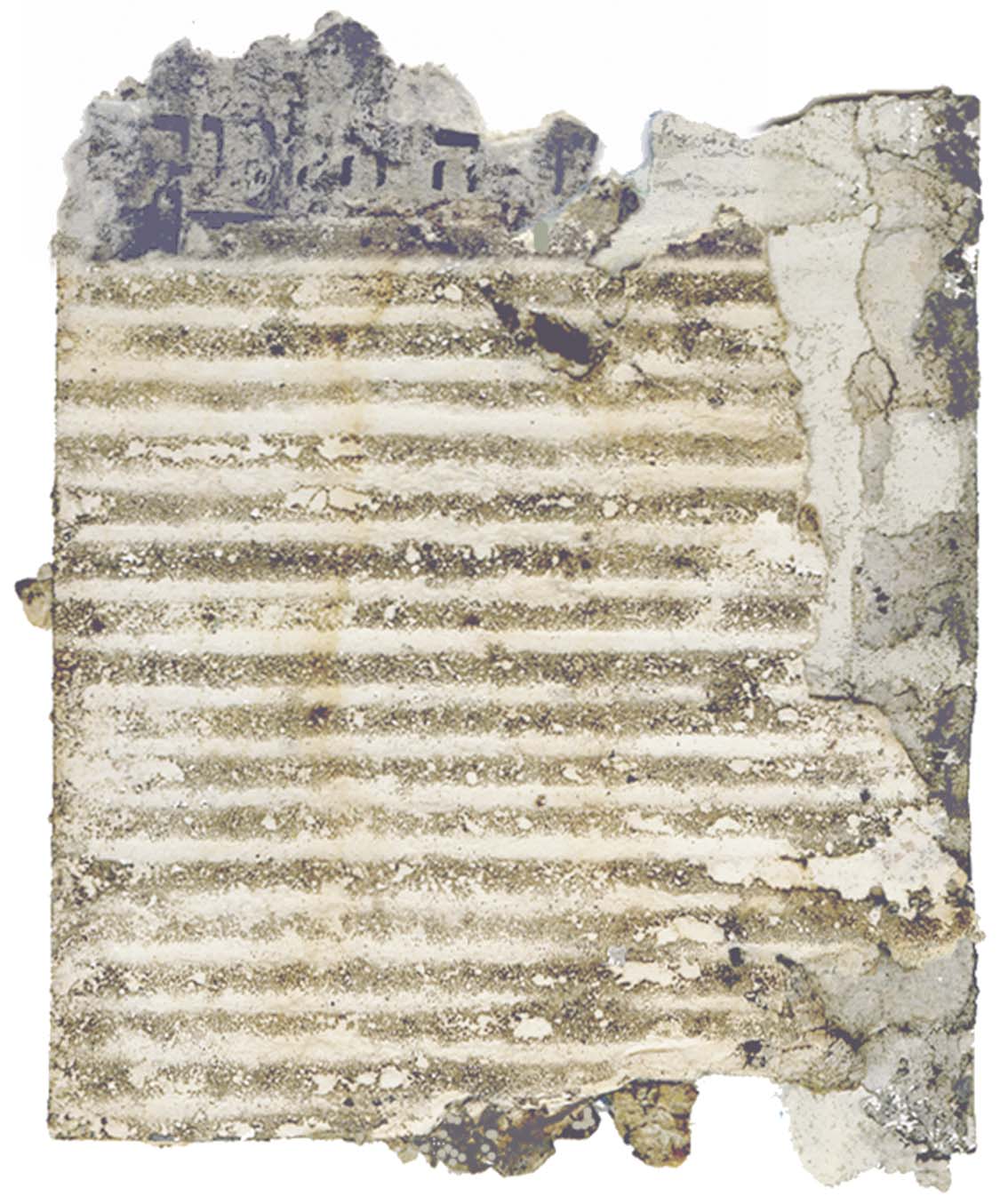

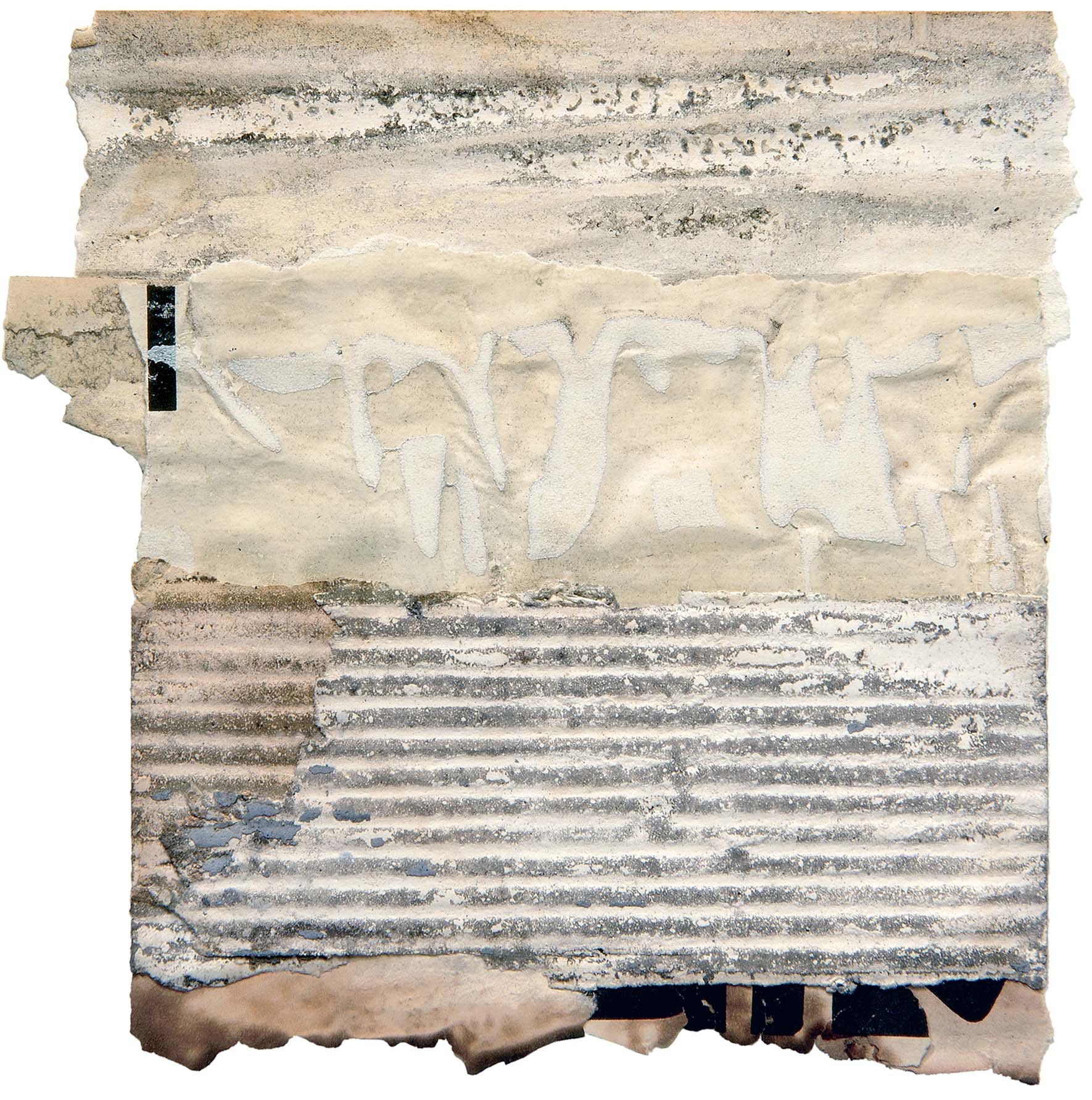

Re'eh: Im Lager

1980

paper

3 3/4 x 3 1/8 in. -

-

Re'eh: The Inconsolable

1980

paper and mimeograph master

12 11/16 x 5 15/16 in. -

Re'eh: Broken Words

1981

paper

3 5/8 x 11 1/2 in. -

Re'eh: Alle!

1981-82/84

paper

5 3/8 x 14 15/16 in. -

Re'eh: Transport

1983

paper and fragments of organic matter

7 1/4 x 18 13/16 in. -

-

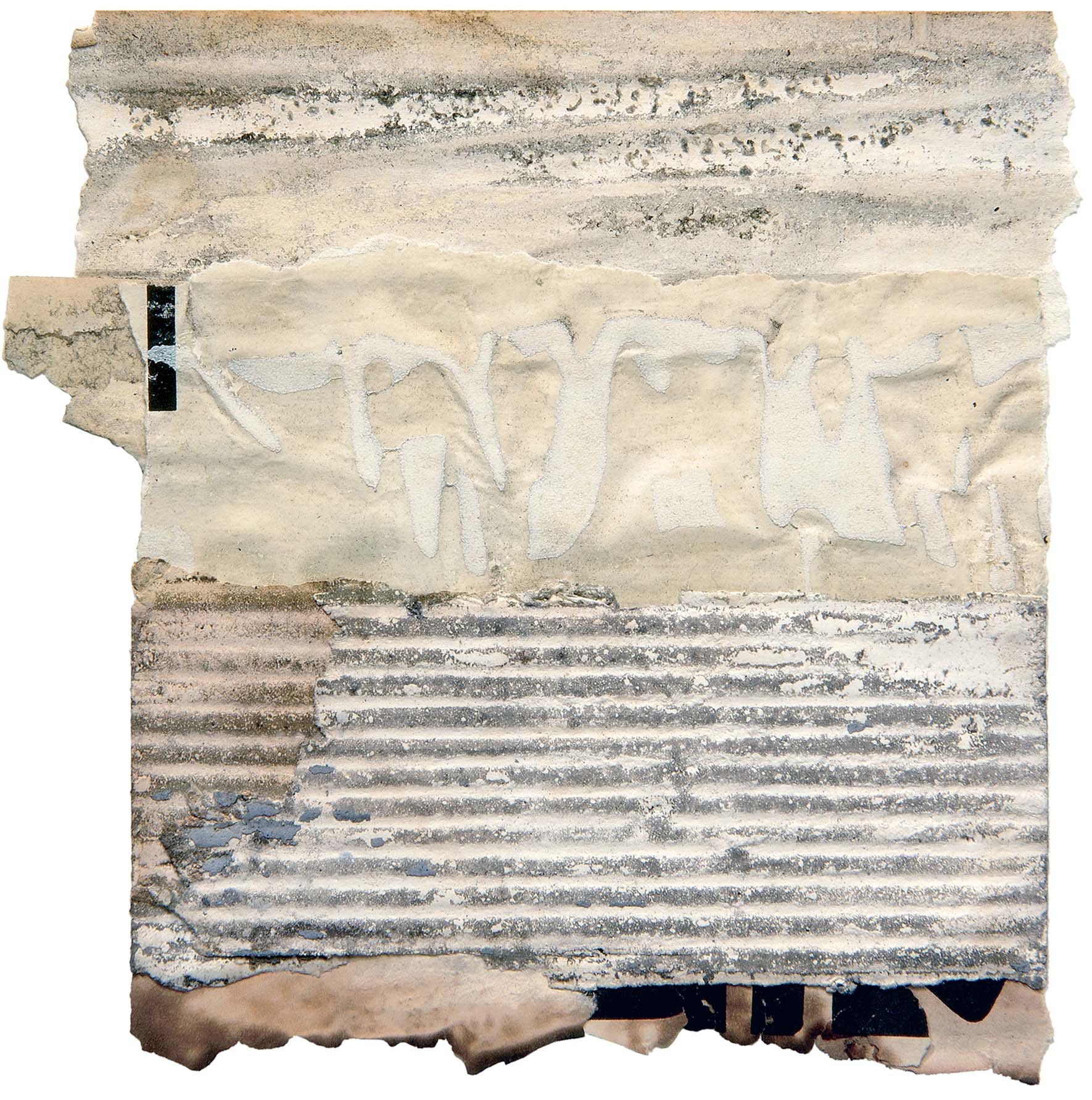

Re'eh: The Three Graces

1982/1984

paper

31 x 16 5/8 in. -

Re'eh: . . . and by Gun

1983

paper and photomechanical transfer paper

3 13/16 x 13 in. -

Re'eh: Panathenaic 807985

1983

paper

3 1/2 x 19 13/16 in. -

-

Re'eh: Ten Is One

1983-84

paper

11 1/16 x 4 7/8 in. -

-

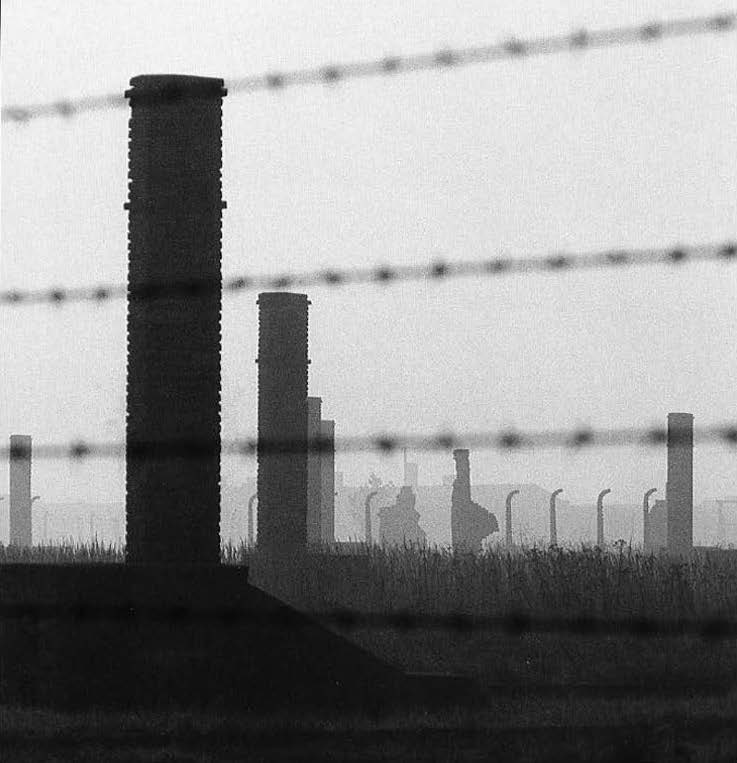

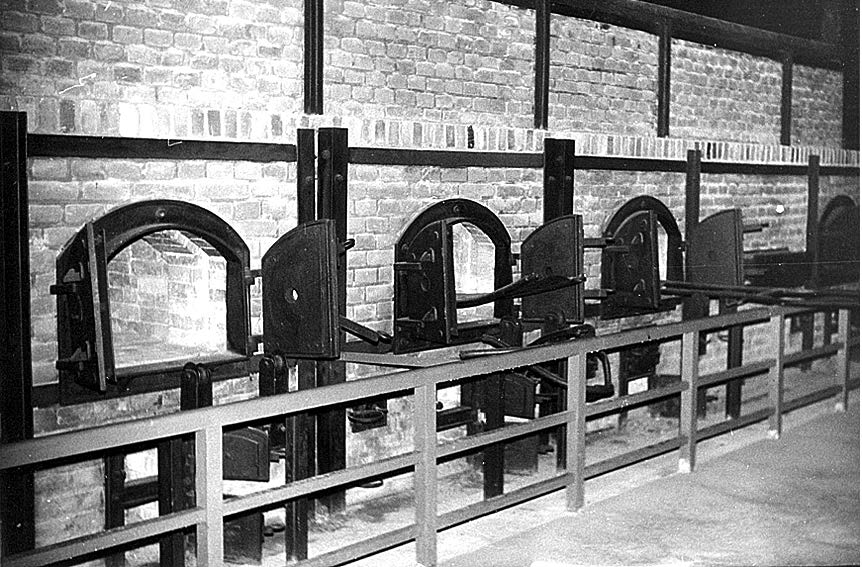

Re'eh: Unto Dust

1985

Tar (?) and paper fragments, blotting paper

12 x 5 1/8 in. -

On the Making of the Re’eh Series and Its Iconography

I: The Making of the Re’eh Series

Re’eh! in Hebrew means “See!”

I think of these Re’eh collages, the group of them, as a monument to the victims of the Holocaust. But from the start, each work arose unintentionally and fit no prescribed program. The making of the series1 came about in this way. . . .

During the winter of 1980, in my distress over the conflict then escalating around the world, I took to working again in my old basement studio, a small, cramped room where many of my early works had been made. I found it enormously comforting to be there, picking through the heaps of paper that I had collected during the seventies in Europe and in New York. But I no longer know exactly how or why I began fiddling with that paper. Perhaps I had gone down to get a screwdriver or, more likely, to crowd into the old studio certain small iron sculptures that I had composed but had not welded. Anyway, I probably began to play idly with some scraps that caught my attention. That's enough to set the process going, after which I get to work more seriously. I clearly remember rushing out at one point to -

fetch my favorite paper-handling tweezers from the main studio, then rushing back to arrange a makeshift workspace with a slab of wood across two cinderblocks for a table and another cinderblock for a chair. At first, I picked through various trays crammed with paper; then, in a frenzy of impatience, I poured the contents of others onto the impromptu table. Thus off and working in a white heat,2 I hardly minded the cramped quarters, and time — the world even — vanished also in my concentration on those vagrant scraps of color.

Arkhe

What work arose first I cannot say, whether Arkhé or one called Black Telos or Im Lager,3 the first of the Re’eh Series. Whichever, as soon as I made Im Lager — no, even as I was working on it (and I went about it no differently from the way I make any collage, that is, without a preconceived image in mind) — I knew that it had to do with the Holocaust, knew it with immediacy. Those stripes! And that shape with its broken Hebrew word! Torah scroll, tombstone? At once, the stripes that were worn in the camps and a scroll whose script is entombed in the same stripes! What else, if not both the camps and the world that the camps destroyed!

-

Black Telos I

Im Lager

-

The collage that lay on the rickety table that wintry night shook me. For one, those referential images violated my own cherished dictum that a collage-of-my-kind should stand for itself and only itself, be a presentation and not a representation. More profoundly moving was the fact that it concerned the Holocaust. I realized that others must follow, though not precisely how many — whether ten, twelve, or eighteen — but that eventually I would complete a group that, taken together, could stand as a monument to the victims. Some days later, after making the second, The Inconsolable, I knew this for a certainty, and I accepted the task in all its gravity, responsibility, and hazard.

The Inconsolable

The horror of the Holocaust, its incomprehensibility, the terrible ordeal of its victims, would occupy an undercurrent of my imagination over the time that would be needed to bring the group to completion. Given the way I work, that could take years — and it did. I accepted also that this work would push against the grain of my own practice, for I would have to make collages given to theme and reference that otherwise I would unquestionably reject. In any case, I resolved to continue working in my usual way, striving always for a collage-of-my-kind and, as it happened, the works that resulted assimilated reference to the nonrepresentational mode.

-

Over the five and a half years that it took to complete the Re’eh Series, I worked on each one much as I did the first, without plan, without obvious design or necessary thematic content. Almost all emerged as I was making other collages, of the kind that refer to nothing beyond themselves. But after having made several, I came to recognize rather quickly when a new work in the series was begun, or was in progress. I don’t think I can adequately articulate what cued that recognition. Palette certainly played a role, yet not a primary one. Mine was a somber palette throughout, one restricted to blacks, whites, grays, and certain browns. I knew early on that

The Three Graces

color would be inappropriate for a collage of this series, knew it without deliberation, much as I know the feel of my right hand without having to think about it. Color would be inconsonant with the nightmarish world that was the Holocaust, would sentimentalize and prettify. Where I deliberately introduce a tatter of color, as in The Three Graces, it serves to reinforce the starkness: the spots of yellow on those desiccated figures call to mind the yellow Star of David that marked a person as a Jew — and so, for annihilation — in the Nazi world.

-

But palette alone could hardly have served as cue that a Re’eh collage was in the making. I’ve made many collages — before, after, and during the making of the Re’eh Series — using a similarly restricted palette. So much so, in fact, that I could mount a sizable exhibit of works entirely in black, white, and gray, exclusive of the Re’eh Series. Such an exhibit would indeed be instructive: similar to the latter in color range and tone, it nevertheless would be strikingly different in feel, in meaning, in visual thrust. These, too, were the touchstones of recognition and contributed to the unity of the series beyond that of palette, a coherence that emerged in its making, or, rather, evolved over the course of the process.

The beginning of any work of mine is invariably nondirective, with no intent other than to make a new collage. As I work along, the many choices — the flux of selection and the shaping of the material — cumulatively assert direction for the particular work in progress. In the special case of the Re’eh collages, that direction was guided in addition by an iconography and symbolism, implicit and nonprogrammatic, that also emerged or evolved, and this integrally, over the making of the series. What I strove for was a synthesis — feeling, thought, and vision hopefully one.

To illustrate what I’ve been describing, here’s how I came to make the collage called Ten Is One . . . . -

Ten is One...

Back in 1983, on the last day of that year, I began to fidget with paper that I had collected in northern Italy seven weeks earlier. I had recently finished the composition of . . . and by Gun and of Panathenaic 807985, and the paper that I was now drawn to was, as in those works, mainly black, white, gray. I remember that I expressly didn’t want to make another Re’eh collage, that I began working prompted by another impulse entirely, namely, to make a work I could give to a brother of mine. But as I worked, the black and whites, their patterning and shapes, began to evoke the idea of people in prayer shawls huddled together. Yielding to the emerging image, I

became more deliberate and composed the collage of ten pieces of paper each differing in its configuration of black or white or of stripes. Why ten? Because ten adults constitute a minyon, the quorum necessary for congregational prayer; and, while it remained abstract, I organized this collage to evoke the sense of such a huddled quorum when seen from

-

...and by Gun

behind. Moreover, it is said that whenever such a minyon convenes, it in effect stands for all of the people, and that exactly — all of the people — was the target of the Final Solution. Thematically, the “all” implicit here in the minyon, as elsewhere in the series, is made explicit in another work, Alle! Nowhere else is a complete word spelled out — broken words4 everywhere, and what of humankind when words shatter? — except for the word kol found in this

Panathenaic 807985

-

collage. Kol is the Hebrew word for “all,” with alle, of course, being the cognate in German and in Yiddish. In Alle!, the complete word, in its isolation, opposes the fragmented letters and broken words that occur in that work and recur through the series.

Not a haphazard iconography, this intermeshing of themes, yet one that burgeoned without forethought. Which in itself shouldn’t be perplexing, since a collage comes out of my living, is a distillate but not a translation of it, however much it swings free of me afterward, deriving significance on its own terms. Im Lager didn’t emerge from a vacuum but from a consciousness sensitized by certain events, certain feelings, certain significances. After it and the next one, I was primed to perceive in

Alle!

-

whatever I was doing, even in my searches for paper,5 the potential for another work of this special kind. And yet I never started a work session saying, today I will begin one of those. Even when picking out whites and blacks to work with, I could never know beforehand that a Re’eh collage would result. The process of making, despite the innumerable analyses about it, remains — thank goodness — a mystery!

For my works other than those of the Re’eh Series, title and collage are perpendicular one to the other, the name being extrinsic and serving as a tag of identity while remaining visually nonspecific. But the title Im Lager functions differently, being integral to the work of that

Unto Dust

name. Without avoiding visual connotation, here, as across the whole series, title serves as cue to the universe of the collage, the “concentrationary” universe. That hellish world is evoked allusively by the scraps of reference, half-effaced and only obliquely suggesting that terrible, ungraspable reality, the reign of death monstrously conceived and rationally executed, referred to now as the Holocaust.

-

I thought I had come to the end of the series when the tenth or minyon collage, Ten Is One, was finished. Then, over a year later, while messing around one day with a heap of scrapings, bits of tar and tiny paper fragments taken from a work that I was preparing for exhibit, Unto Dust materialized. Upon that I knew the series to be complete. What, after all, could follow?

The Re’eh Series is always exhibited alone, in its own space separated from all other art. This holds even when the series is shown concurrently with other work of mine at the same museum. Either a room is provided for it alone or a walled enclosure is built for it in the gallery. A space is thus delineated distinct from the quotidian; there, the Re’eh collages set the ambience.

Let the visitor experience what he or she may.

Look! Witness! Remember!Durham, North Carolina

November 1989 -

II: The Iconography

Not a haphazard iconography, as I said, but one of intermeshing themes that burgeoned without forethought over the years I worked on the Re’eh Series. The visual content of the collages — what’s immediately perceivable — are condensations of certain underlying images and ideas. These elements — from symbol, lore, ritual, and historical events, and from Grecian, Christian, and Renaissance art — inform these collages and are detailed below. But “inform” is not the same as “mean” or “account for” or “explain.” What follows is an inventory, collage by collage, of the iconographical elements underlying each and of their repetition and commingling throughout the series.

Above all, the Re’eh Series comes out of my experience — this, on many levels of functioning. As a requisite for making it, I need not have been a survivor myself nor had relatives who were exterminated in the Nazi conflagration. Merely to be human was reason enough to grasp something of the enormity of the Holocaust, if only imaginatively from reports and photos that appeared after the war, and to be transformed, as I completely was, by knowing of it. By “underlying” I do not mean that I worked directly from such images as are illustrated below. I assembled them to make this presentation accessible to others. For myself, I had no need to inspect a photo of a minyon to know how one appears visually from the back, nor of -

a Chasid dressed in caftan and shtreimel.6 These, as well as much else that I describe below, I had experienced over and over again when growing up in Chicago.

Nor, when composing certain of the collages, did I have to learn about, or seek out reproductions of, art images associatively related to them, whether a painting by Piero della Francesca in Tuscany or certain Cranach nudes or a Pontormo fresco in Florence or sections of the Elgin marbles or a Botticelli painting in the Uffizi, for these are works that I held well in mind, having seen each several times in situ. I did not ask to make these works, I did not plan them. They emerged nonvolitionally within the stream of my artistic activity many years later and after I had gained further knowledge about that extreme horror of history. The photos from the concentrationary world given below are taken from several sources to illustrate some aspect of, or idea relevant to, a collage and are not necessarily those I saw in the forties or became familiar with at any time afterward, up through the completion of the Re’eh Series in 1985.

Though I call this an iconographical inventory, my presentation is expository, as I do not avoid drawing out what certain of the condensations suggest or mean. But those are not necessarily exhaustive, and this inventory could provide the bases from which to move toward a more general interpretive analysis. I say “move toward,” by which I do not -

mean “arrive at” any definitive meaning, either for individual works or for the Re’eh Series as a whole. Singly or collectively, these works remain finally themselves, unsnarable by nets of words alone. I must insist, however, on one matter and this most emphatically. Because of the nature of what I was portraying, I had to make free use of religious imagery and symbols, mainly but not exclusively Judaic. In doing so I assuredly do not affirm any faith or any divinity — if anything, the reverse. To read it otherwise is seriously to misunderstand, distort, and neutralize the thrust — as intended by me — of the Re’eh Series.

In the account that follows, I make reference to illustrations that “inform” a collage’s image. The sources of these illustrations are given in the photographic credits at the end of this catalogue. Explication of the three collages discussed in part 1 of this essay — Im Lager, Alle, and Ten Is One — will be repeated, either modified or expanded, to provide their relevance within the sequence as a whole. The order of the collages as here presented is that of their making; in exhibitions, I vary the order slightly for visual reasons.

-

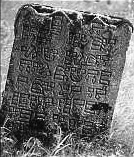

Im Lager

“In the Camps,” cued immediately by those salient gray stripes, garb of what was destined for extermination (fig. 1) — an entire people! An entire culture, too, as the stripes encase what the shape itself harbors — a Torah scroll (fig. 2), a Dead Sea scroll (fig. 3), and the Decalogue (fig. 4), sacred documents at the core of Judaic identity, each here structurally shattered. And further, the form of the three, enshrouded in the stripes of the camps, of what was a huge cemetery, condenses yet a fourth image, that of an old Jewish gravestone in Germany (fig. 5). -

The formal similarity between Im Lager and those four underlying images can be examined by comparing the collage with those figures (2 through 5) along with that for figure 6. The collage represents a Torah scroll simultaneously in its closed and in its open form via the condensation of several images into the one. Thus, figure 6 shows a Torah scroll with its two sides rolled tightly together and encased in a velvet coverlet, much the way one is housed in a synagogue’s ark or, as in this figure, carried in procession during prayer services. The right-hand third of Im Lager resembles the shape of one side of such a closed scroll, though missing the rolling handle. In turn, the area at the top left of the collage is reminiscent of a crown that adorns a Torah when closed. A scroll is opened during a service for reading and afterward is held aloft

fig. 1 Yoked in stripes

fig. 2 A desecrated Torah scroll

fig. 3 A Dead Sea scroll

-

fig. 4 The Decalogue represented

on a Torah Mantle

fig. 6 A Torah scroll in

velvet coverlet carried

during a service

fig. 5 A Jewish gravestone

in German -

before the assembled congregation prior to being rolled closed again. The collage’s resemblance to the open state is conveyed in several ways: by its general form and proportion; by the Hebrew letters at the top on the left; by the stripes, which, in addition to their other significances, resemble lines of script seen by congregants at a distance when an opened scroll is held aloft. In appearance, then, the collage represents a text that has already been read and, in fact, is now unreadable, the Hebrew letters forming no word, though an inference can be made from what is discernible — hei, vav, hei — the last three of the four-lettered Ineffable Name, Yehovah. The Tetragrammaton fragmented!

Being prime symbol of the Mosaic Law, the Decalogue is usually represented on a Torah coverlet, as shown in figure 4, and often appears as an emblem on or near the doors of the ark that houses Torah scrolls. The overall shape of Im Lager hews closely to it as conventionally depicted in both Jewish and Christian representations; what should be a round arch appears to have been broken off or shattered at the top right. Resemblance of the collage to a Dead Sea scroll (fig. 3) and to a gravestone (fig. 5) is noteworthy.

-

-

The Inconsolable

A black grief irremediable7 in the form of a Chasid (a member of a sect generally lead by a wonder-working rabbi) in traditional caftan and shtreimel, as shown in figure 7. Long are the tears that drip from him, as long as the white tzitzis8 of a fringed garment that he surely would be wearing. Hunchbacked, or bearing a huge burden, conceivably harboring a group of Jews, perhaps a minyon, hiding within his caftan, the persecuted much like those in Christian depictions of the Madonna of Mercy, an example being that by Piero della Francesca (fig. 8). At the bottom, the Hebrew letter hei appears again, broken, not once but twice, as are ordinary words, too, their letters haphazardly strewn across the Chasid’s shtreimel.

fig. 8 The Madonna of Mercy by Piero della

Francesca, main panel of the Misericordia

alterpiece, Pinacoteca, San Sepolcro

fig. 7 A Chasid in kaftan and streimel

-

Broken Words

Indecipherable letters, some seem like Hebrew,9 broken words again, if not broken promises also!10 What of humankind when words shatter? Are they people, these marks that appear to march in procession (fig. 9) on ridges over an abyss? Or are they lined up for execution over an open pit (fig. 10)? Or entering some black maw (fig. 11)?

fig. 9 En route to "resettlement," meaning to

a camp, thence to death

fig. 10 On the rim of the execution pit

fig. 11 A gas chamber

-

Without a Name

In the concentrationary world, a myriad died without remembrance, their names as lost as though embossed in sand or formed from dust or charred by flame, lost as would be the meanings of some proto-Semitic script. In this work, seemingly ancient writing fills its central portion; a hei and a fragment of another, both formed from dust, can be seen at its top; unreadable letters peep out on its charred paper at the bottom. The stripes of the camps corral the whole. And in those camps tattooed numbers replaced names — one of many stratagems devised to destroy a person’s sense of self.A subtle feature of this collage’s title has relevance to the Tetragrammaton and needs comment. Jews are forbidden to pronounce the word formed by the Hebrew yud-hei-vav-hei (Yehovah). In liturgical settings and in prayer a substitute is enunciated instead, the Hebrew word meaning “my Lord” (Adonai); in nonliturgical usage, the word hashem serves the same purpose and it means “The Name.” But the title’s shift to the indefinite article finesses the meaning significantly. Two prior collages represent “The Name” as broken or fragmented, hence inefficacious. Implied here is that the tattooed ones in the camps are without the benefit of any Name, any divinity.

-

Alle!

Isolated letters spread out like people for execution, though among them, exposed also, stands the only complete word in the series, the Hebrew kol, meaning “all.” The Final Solution targeted for extermination “all” of the Jewish people — kol k’lal Yisroel — alle in German, alle in Yiddish, kol in Hebrew. In Weil’s Dreigroschen Opera, when the pirates ask Jenny the Whore whom they should kill, “Alle!,” she tersely commands. The form of the collage, with its vertical striations, suggests a barricaded camp, where indeed death was its function (fig. 12).

fig. 12 Its function — death!

-

Transport

Central to the Final Solution’s task of slaughter was the German railroad network. It carried the victims to the camps like cattle in boxcars (figs. 13 and 14). So systematically was this carried out that each victim was issued a railroad ticket and the enterprise fiscally accounted for via double-entry bookkeeping. A lettered people, those of the Book, peer out at the cramped opening. Organic insect parts splatter the boxcar’s side.

-

fig. 13 To the death camps in an open cattle car

fig. 14 Disembarked from closed cattle cars,

awaiting “selection” -

. . . and by Gun

In the sights of gleaming guns, mechanically precise, accurate to the mark, the crosshairs fix on a group of letters, the Hebrew yud, whether in a shtetl on a hill or perched at the edge of a mass grave (fig. 10). Condensed in this image is a verbal cluster: yud of Yehudi (yud-hei-vav-daleth-yud, which is “Jew” in Hebrew); yud of Yid (yud-yud-daleth, which is “Jew” in Yiddish); . . . yud of Yehovah (yud-hei-vav-hei, the Tetragrammaton) . . . blown away (fig. 15)!

-

fig. 15 Murder whenever and however

-

Panathenaic 807985

The stately parade of maidens during the Panathenaic games, as in a frieze from the Parthenon (fig. 16). A later procession (fig. 9), the doomed march of tattooed arms to the crematoria (fig. 11). Poles apart! What “civilized” nation admired Greek culture more than the German?

fig. 16 Maidens in Panathenaic procession, from the

frieze of the Parthenon, Louvre, Paris -

The Three Graces

Aglaia (Brilliance), Euphrosyne (Joy), Thalia (Bloom), leaveners of life and nature, bestowers of pleasure, charm, and beauty, so sensuous in their diaphanous gowns and dancing, as painted by Botticelli (fig. 17). But in and after Auschwitz, desiccated, punctured, ghostly, bearing tatters of the yellow Magen David,11 badge of a Jew (figs. 18) . . . and with Cranach’s hat askew (fig. 19). -

fig. 17 The Three Graces, detail from

Botticelli’s “Primavera,” Uffizi, Florence

fig. 18 Labeled in yellow

“for extermination”

fig. 19 The rakish hat in Lucas Cranach’s The Judgment of Paris,

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York -

Ten Is One

A minyon huddled in prayer, as seen from the back (fig. 20), in spirit kol k’lal Yisroel, the alle destined by the Germans for annihilation and a quorum, as imagined hidden under the Chasid’s caftan of The Inconsolable. Each communicant drapes a prayer shawl (tallis) over the head and, unless it is the Sabbath or a holy day, wears phylacteries (tefillin) on forehead and left arm (fig. 21).

fig. 20 A minyon seen from the back

fig. 21 In prayer shawl and phylacteries

-

Unto Dust

Corpses feed the ovens ceaselessly (fig. 22); their ashes spew inchoately from the chimneys (fig. 12). In what appears at first glance to be but random drift of soot, closer inspection can discern a human form configured in the rising dust. Multiple images contribute to its significance. The stance of that ghostly form, and especially the shape I wrought from dust for its right leg, calls to my mind that of the Angel of the Annunciation in Pontormo’s great triptych at Santa Felicità in Florence (fig. 23). At the top’s small black segment, a cluster of images is condensed: a skull and a form that represents both a square skullcap and a tefillin box.

fig. 23 The Angel of the Annunciation by Pontormo, Capponi Chapel, Santa Felecita, Florence

fig. 22 Crematorium ovens

Phylacteries are worn in such a way as to be close to brain and heart. No mere boxes, in them are contained passages from the Torah that declare the absolute unity and oneness of Jehovah. Chasidim and some Orthodox Jews, both before wrapping themselves in a tallis and before putting on the tefillin, recite a special declaration known as l’shem yichud, for the sake of the unity of the Name (yud-hei-vav-hei). But murderous German soldiers mock the Jew, in tallis and tefillin, reciting the prayer for the dead (Kaddish) over corpses of those recently executed, his tefillin desecrated and split open (fig. 24), sundering the unity of yud-hei with vav-hei.

Berkeley, California, summer 2001

Durham, North Carolina, summer 2006

fig. 24 Mocked by German soldiers, his phylacteries

split open, praying for the recently executed -

1. Part 1 of this essay rests upon a previous one, “I & K: The Second Dialogue,” which appeared in the catalogue In Plain View: The Collages of Irwin Kremen (Memphis, Tenn.: Memphis Brooks Museum of Art, 1987). It revises the latter in form, adds and expands other material, and eliminates considerations not relevant to the Re’eh Series. The revision, under the title “On the Re’eh Series and Its Making,” has appeared under the same title in the catalogues that accompanied exhibits of the Re’eh Series at the Wichita Art Museum (From the 2nd Decade: The Re’eh Series [Wichita, Kans.: Wichita Art Museum, 1990]) and the Telfair Museum of Art (The Re’eh Series, Collages by Irwin Kremen: In Memory of the Victims of the Holocaust [Savannah, Ga.: Telfair Museum of Art, 1999]). Part 2 has not appeared before.

2. See “I & K: The Second Dialogue,” 8, for a discussion of this “state.”

3. The full title of each work in this series begins with the word Re’eh, e.g., Re’eh: Im Lager. The initial word is dropped in the text of both part 1 and part 2 of this essay for the sake of expository brevity.

4. The title of a collage in this series.

5. The papers bearing Hebrew letters weren’t collected with the Re’eh Series in mind, but for a different purpose entirely, in August 1979 on a search of the Williamsburg section of Brooklyn; thus before the making of Im Lager by eight months.

6. The word shtreimel refers to the kind of fur hat worn by Chasidim.

7. The novelist Bernard Malamud, seeing this collage in my studio, remarked that it invoked a “great grief” in him. That became cue to the title.

8. The word “tzitzis” refers to the long knotted threads that hang from the four corners of a prayer shawl or a fringed garment. Tzitzis symbolize via a recondite computation the 613 divine biblical commandments.

9. English letters altered by me to be Hebrew-appearing.

10. By politicians.

11. See a fuller description in part 1. -

Photographic Credits

The list below presents the copyright permissions received for photo images reproduced herein:

Fig.1, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM), courtesy of National Archives and Records Administration, College Park

Fig. 2, USHMM

Fig. 3, The Bialik Institute and the Hebrew University, Jerusalem (applied, permission pending)

Figs. 6, 7, 21, © Mara Vishniac Kohn, courtesy International Center of Photography, photos by Roman Vishniac

Figs. 8, 16, 17, Scala/Art Resource, NY

8. Piero Della Francesca, Madonna della Misericordia, Pinacoteca Communale, Borgo san Sepulcro

16. Procession of the Panathenean Games, east frieze of the Parthenon, Musée du Louvre, Paris

17. Botticelli, the Three Graces, detail of La Primavera, Uffizi, Florence

-

Fig. 9, USHMM, courtesy of Instytut Pamieci Narodowe

Fig. 10, USHMM, courtesy of Zentrale Stelle der Landesjustizverwaltungen (Bundesarchiv)

Fig. 11, USHMM, courtesy of Panstwowe Muzeum na Majdanku

Figs. 13, 15, 22, 24, Photo Archive, Yad Vashem, Jerusalem

Figs. 14, 18, USHMM, courtesy of Yad Vashem (Public Domain)

Fig. 19, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Roger's Fund. Scala/Art Resource, Lucas Cranach, The Judgment of Paris

Fig. 23, Nimatallah/Art Resource, NY, Pontormo, detail, angel of the Annunciation, S. Felicita, Florence

Not enough information to locate the copyright holder: Fig. 4; Fig. 20;

Fig. 5, Photo by Arnold Schwartzman;

Fig. 12, Photo by Adam Pujak

Photography: the Re'eh collages, by Peter Geofrion

Copyright Re'eh collage images and essays (Parts I and II): ©2007 Irwin Kremen -

Exhibitions of the Re’eh Series

Rose Art Museum, Brandeis University, Waltham, MA, 1985

Allentown Art Museum, Allentown, PA,1985

Memphis Brooks Museum of Art, Memphis, TN, 1987

Gallery 400, University of Illinois at Chicago, 1988

Wichita Art Museum, Wichita, KS, 1990

Ackland Museum of Art, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, NC, 1991

Archer M. Huntington Art Gallery, University of Texas at Austin, TX, 1992

Green Hill Center for North Carolina Art, Greensboro, NC, 1996

Telfair Museum of Art, Savannah, GA,1999

Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University, Durham, NC, 2007